If my 3rd great-grandfather hadn’t made one small choice, my family tree today would look completely different.

Ambroise Abraham Richard was born on 12 June 1815 in Saint-Denis-sur-Richelieu, Lower Canada (Québec), a small parish along the Richelieu River. He was born to Marie Charlotte Archambault, age 26, and Pierre-Antoine Richard, age 20. At that time, Saint-Denis-sur-Richelieu was a well-established French-Canadian community, part of the seigneurial system that had dominated southern Quebec for centuries. Settlers had arrived as early as the 1600s, farming the fertile land, building churches, schools, and a tightly knit village society.

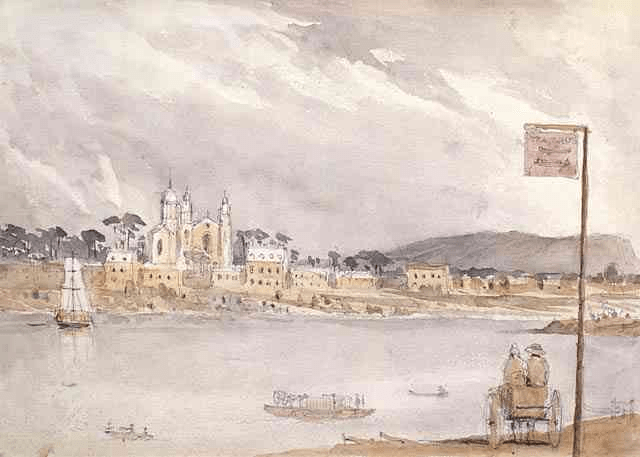

By 1815, the parish had a strong French-Catholic identity. Ambrose was baptized into this world the same day he was born (at Église de Saint-Denis), surrounded by families who had been there for generations. Names like Richard, Boucher, Gagnon, and Côté were common. Life was centered on the parish church, seasonal farming, and local trade along the Richelieu River, which was itself a vital route for commerce, travel, and communication between the St. Lawrence River and Lake Champlain.

Library and Archives Canada, Acc. No. 1983-47-63

When Ambrose grew up in Saint-Denis-sur-Richelieu, it would have looked peaceful enough. A river town. Church on Sunday.

People talked here, not just about weather or crops, but about power. About who made decisions and who didn’t. About being a French-speaking, Catholic majority governed by a British colonial elite that controlled land, laws, and political institutions. After the British conquest of New France, French-Canadians remained rooted to their farms and parishes, but real authority sat elsewhere, with governors, appointed councils, and officials who did not speak their language or share their customs.

Political ideas weren’t abstract. They were practical and personal. They were discussed after Mass, muttered in kitchens, debated in taverns. People talked about unfair taxes, land policies, and laws passed without their consent. They talked about how petitions were ignored and elected assemblies overruled. Even if a child didn’t understand the words, they understood the tone — the frustration, the resignation, the simmering anger that something wasn’t right.

By the 1830s, that tension had hardened. Reformers in Lower Canada, known as the Patriotes, demanded responsible government, the right for elected representatives, not British-appointed officials, to control public spending and laws. When those demands were rejected, protests spread through the Richelieu Valley. Saint-Denis-sur-Richelieu became one of the centers of resistance.

In November 1837, that unease broke open. Saint-Denis was the site of one of the first armed confrontations of the Lower Canada Rebellion. Local men, farmers, notaries, shopkeepers, neighbours, took up arms against British troops. Against expectation, they won the battle. For a brief moment, it seemed possible that ordinary people could push back against imperial power.

It didn’t last.

British forces regrouped. The rebellion was crushed. Leaders were executed or exiled. Homes were burned. Entire communities were punished to make an example of them. The message was unmistakable: resistance would be met with force.

But the memory stayed.

It stayed in families, in parishes, in the stories told quietly and carefully. It stayed in the understanding that speaking too loudly carried risks and that survival sometimes required adaptation rather than confrontation. Ambrose didn’t need to fight to be shaped by it. He grew up in a place where people had learned, painfully, the limits of defiance and the cost of being on the wrong side of power.

That’s the part that matters to me.

Because when we talk about someone’s “choice,” we often imagine freedom, open roads, equal options. But Ambrose’s world didn’t offer that. His choices would have been made in narrow spaces, under pressure, with consequences that stretched beyond him.

And once you see that, you start to wonder:

What would I have done, knowing what he knew and what he didn’t?

Why Move West?

After the rebellions, there was also a quieter pressure … political fatigue. The loss lingered. So did the consequences. Some people stayed and adapted. Others learned that keeping your head down was safer than speaking up. And some began to look elsewhere, not out of rebellion, but out of necessity.

It wasn’t an easy choice, I’m sure. Leaving meant walking away from family, parish, language, and everything familiar. It meant becoming an outsider. But staying carried its own risks: stagnation, dependency, and the slow narrowing of options.

So why Bathurst, Ontario, in the late 1830s? Several factors likely played a role:

- Land and opportunity

- Québec’s seigneurial system meant that land inheritance was limited, especially for younger sons. Farming families often could not support all their children on the same land.

- Upper Canada (modern-day Ontario) offered larger plots of land through grants and settlement programs.

- Economic mobility

- The Ottawa Valley and Bathurst District were frontier regions that grew rapidly in the 1830s, offering opportunities in logging, farming, and trade.

- Ambrose, as a young man, could establish himself independently, rather than remain tied to his family’s parish land.

Marriage:

Ambrose married Olive Moore on 1 Jan 1838 in Bathurst, Ontario. Olive was born in 1821 and descended from a Loyalist (UEL) family who moved from the United States after the fighting in the American Revolution. For my very own Outlander story, read the three-part series here, here, and here. The ceremony was witnessed by Roger “Moor” and another “Moor” whose name is difficult to decipher. Marrying Olive connected Ambrose to an English-speaking, Loyalist-descended family, providing both social integration and stability in his new community.

Settling in Eardley Township

Ambrose and Olive moved to Eardley Township, Québec, just over the Ottawa River from Ontario. What drew them there?

- Available land: The government of Lower Canada was granting land to settlers along the Ottawa River, especially in the 1850s and 1860s.

- Economic opportunity: The Ottawa Valley was booming with logging, farming, and trade, especially along rivers and near mills.

- Community networks: Many settlers in Eardley had come from Québec and Upper Canada, so Ambrose could be near people he knew or who shared his culture and religion.

- Frontier independence: Life in Eardley offered more freedom to make personal choices, from religion to family decisions, than the old Richelieu parish ever could.

The challenges were significant:

- Settlers dealt with poor soils, distance to markets, and the general harshness of the new country.

- Limited road networks meant many areas were isolated, although new roads began to improve access.

- The 1860s were generally a period of steady, if slow, settlement progress.

Land grant vs. census name:

Official records show Ambrose Richards as Ambroise Richard in his 1859 Québec land grant, which granted him 100 acres in Eardley Township. By the 1861 census, however, he is listed as Ambroise Richards, showing that the anglicization occurred between these two records and later anglicized his first name to Ambrose, from Amboise. This change was practical and social, likely influenced by his marriage to Olive Moore, daily life in an English-speaking community, and interactions with clerks and neighbours. By the next generation, the surname Richards was firmly established.

The Choice That Stuck

That one letter followed all his descendants. Every document from that point forward, from censuses to land records, reflected the new spelling. By the time I came along generations later, our surname was solidly Richards, a permanent marker of Ambrose’s choice.

Ambrose’s choice reminds us that even the smallest decisions … how we spell our names, which records we enter, how we adapt to a new community, can shape the legacy we leave. In genealogy, these little details often carry the greatest weight.

- A single letter can alter a surname forever.

- Migration decisions can reshape family history.

- Cultural adaptation can leave permanent traces in records.

Ambrose’s choice was simple, personal, and deliberate, and its consequences echo through generations. One letter, one decision, and a family name was forever changed. That is the power of choice and the story of my family’s identity.

Final years:

Ambrose lived out his remaining years in Eardley Township, Québec, farming and raising his family. He passed away on 9 January 1864.

By at least 1880, we know that Olive had crossed the border into the United States, settling in Ogdensburg, New York, with her two youngest children, Olive and John. Though living in an English-speaking country, both children retained their French surname, recorded as Richard (see Olive Jr.’s headstone below vs her mother’s), a quiet reminder of their origins and their father’s heritage. Olive rebuilt her life and married John O’Hagan. She remained there until her death on March 22, 1898.

Leave a comment