As I continue to explore my family’s history, I’m continually struck by the remarkable ways in which personal stories intersect with larger chapters of world history. One of the most intriguing threads leads back to a tiny settlement in Ramsay Township, Ontario, called Bennie’s Corners.

Today, few people likely recognize the name. But anyone who has ever dribbled a ball, watched a buzzer beater, or felt the electricity of a packed stadium owes something to this quiet rural crossroads. After all, Bennie’s Corners is where the inventor of basketball, Dr. James Naismith, spent a defining part of his boyhood.

Even more fascinating is that my own family, the McKenzies, lived right there among the settlers who shaped that community.

And so, an irresistible question emerged: Could my ancestors have known, gone to school/church with, interacted with, or even influenced the young James Naismith?

And the more I dug, the more jaw-dropping it became. My McKenzie ancestors lived inside the very same tiny Scottish settlement that shaped James Naismith’s childhood.

This is their story and mine.

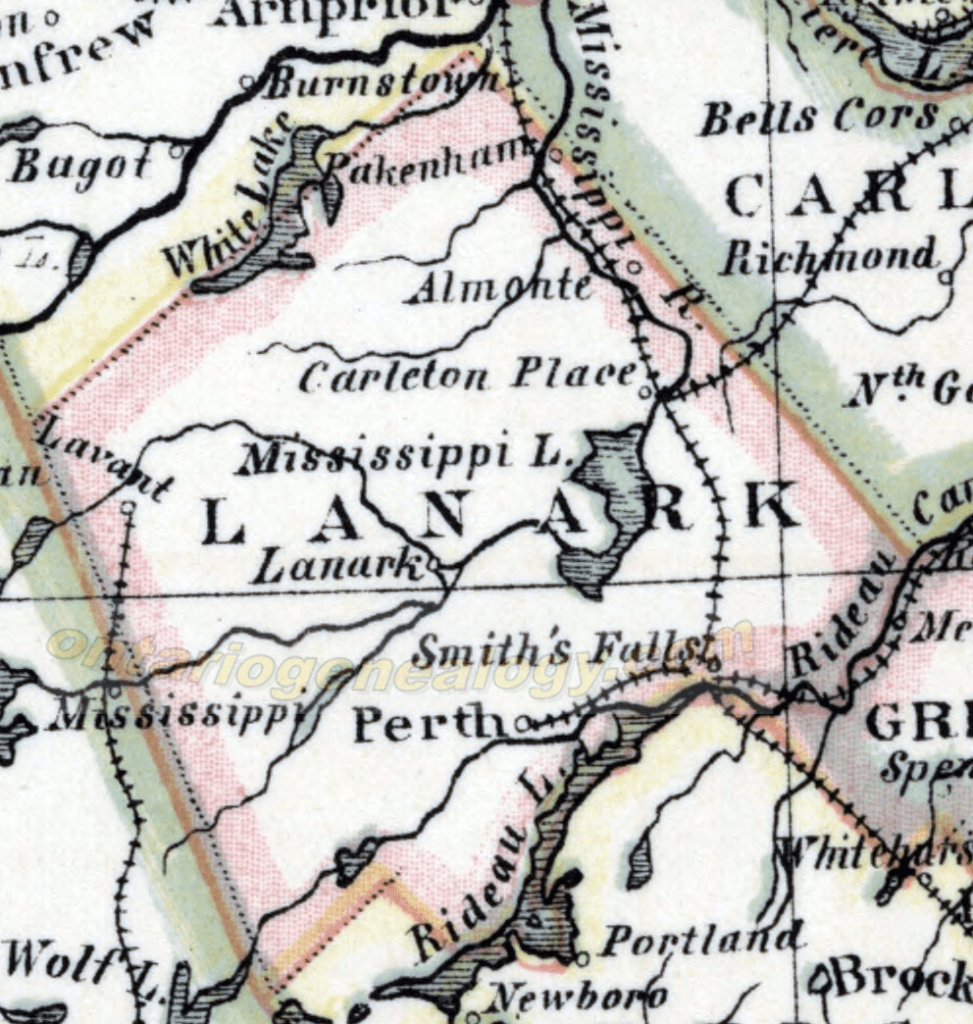

The Scottish Enclave of Ramsay Township

In the 1840s–1870s, Ramsay Township was one of the most concentrated Scottish diasporic enclaves in the Ottawa Valley. Life there was unmistakably Scottish:

- Gaelic and Lowland accents filled the concession roads.

- Presbyterianism shaped daily life.

- Free Church values thrived following the 1843 Disruption.

- Stone houses, shared labour, and close‑knit kinship networks defined the landscape.

The familiar surnames appear over and over in church registers, land deeds, local school logs, censuses, and the 1879 Belden Atlas: McKenzie, Naismith, Young, Gemmill, Yuill, Baird, McLaren, Snedden, Toshack and Affleck.

They married into one another.

They farmed beside each other.

They built the schoolhouse, the mills, the roads, and the churches.

This wasn’t just a settlement; it was a community in the truest Scottish sense.

Through marriage, relocation, and community ties, my Leckies became part of this web; even though they weren’t the same Leckies associated with “Leckie’s Corners.” My ancestors entered the Ramsay cluster when Agnes Leckie, my 3rd great-grandmother, married Andrew McKenzie II, whose family lived right in the heart of this Scottish settlement.

The Moment Everything Clicked

Everything came together the moment I zoomed in on the 1879 Belden Atlas and saw:

👉 R. McKenzie (my 2nd great granduncle) — Lot 26 West, Concession 7.

Right abutting up to it?

👉 S. Young – James’ maternal uncle

(R. McKenzie highlighted in yellow)

That means:

👉 James Naismith’s childhood home was literally beside my ancestors’ land.

Not miles away.

Not across a township.

Next door.

This wasn’t a vague “same township” connection; it was a fence-line relationship.

NB: My 2nd great-grand uncle received the last from his father, my 2x great-grandfather.

James Naismith’s Childhood And My Family

James was born on 6 November 1861, near Bennie’s Corners, to John and Margaret Young Naismith.

At age six, James was orphaned. He and his siblings were then taken in by their uncle, Samuel Young, Farmer, Concession 7, adjacent to Lot 26 (McKenzie owned land)

James lived on that farm from 1868 to ~1879; some of the most formative years of his life, he:

- Attended S.S. No. 10 Ramsay – Bennie’s Corners School until ~1875

- Went on to Almonte High School

- By 1879–81, he was at McGill University

So, for roughly 11 years, he grew up beside my family.

Schoolmates Almost Certainly

Rural Ontario schooling in the 1860s began around age six in a single-room schoolhouse:

- Older pupils sat in the back, younger near the stove

- Everyone recited aloud — catechism, spelling, arithmetic

- Older students helped younger students with lessons

My ancestors who were likely in the same school room as James:

- Mary McKenzie — b. ~1860

- Sarah McKenzie — ~b. 1862

- Andrew McKenzie — ~b. 1866

- Robert McKenzie — ~b. 1864

I can practically see them there, little slates in hand, reciting lessons aloud, older kids helping younger ones, learning together. This wasn’t Toronto or Montreal. This was a school district of maybe 30–40 families. Everyone knew everyone.

Arriving from Scotland, John McCarter taught in a log school at Bennie’s Corners from 1852 to 1865. Remarkably, one-third of the building served as his living quarters, while the remaining two-thirds was the classroom; a true testament to the dedication of early rural educators. Largely self-taught, McCarter went beyond the basics, teaching subjects like Euclid and Latin grammar to eager local children.

From 1875 to 1888, Thomas Caswell took over, instructing students in Latin, logic, and higher mathematics.

Duck-on-a-Rock — The Game That Inspired Basketball

One of James Naismith’s most well-known childhood memories is playing a game called “duck-on-a-rock,” a medieval Scottish game involving throwing stones at a target rock to knock a smaller stone (“the duck”) off the top.

This is crucial to his later life because, in 1891, at Springfield, Massachusetts, duck-on-a-rock became the conceptual inspiration for basketball.

Here is the part people forget: Duck-on-a-rock was a common rural children’s game in 19th-century Scottish Canadian settlements.

(AI Image)

Scottish immigrants brought the game with them, and it was widely played in:

- Lanark County

- Glengarry

- Renfrew County

- The Scottish concessions of eastern Ontario

So, when James later said he played it as a child, he wasn’t inventing a quirky childhood anecdote. He was remembering a standard rural game Scottish children played throughout the Ottawa Valley.

And here is where the story becomes goosebump-worthy:

My McKenzie ancestors … Scottish immigrants living in the same tiny community would have played the exact same game and likely with him!

Farm Life: Chores, Harvest, and Community Work Bees

Life in Ramsay required interdependence: Neighbours relied on each other for:

- Raising barns

- Harvesting oats and hay

- Splitting rails

- Hauling firewood

- Sharing blacksmith tools

- Borrowing horses and wagons

- Midwifery and childcare

Children were part of this world just as much as adults:

- Fetching water

- Gathering eggs

- Helping with planting

- Driving cows to pasture

- Picking stones from the fields

- Running messages between farms

It is almost guaranteed that the McKenzies (and Leckie) and Youngs worked side by side during seasonal “bees” … big communal workdays where everyone helped each other finish a major task.

That means James would have been present at these gatherings, learning from older children and watching the older McKenzie boys handle horses, tools, and equipment.

Church Life — The Social Hub of Scottish Ramsay

Church was not optional in 19th-century Scottish communities.

It was the central social institution.

My ancestors and the Naismith/Youngs would have attended:

- Auld Kirk (Concession 8)

- St. Andrew’s Presbyterian, Almonte

Children like James and my McKenzie (and Leckie) relatives:

- memorized the same catechism

- attended Sabbath school together

- walked home on the same concession roads

- shared holiday events and church picnics

Church events were major community gatherings, which were sometimes the only chance in the week to see everyone.

Seasonal Social Life

Lanark County Scottish settlers preserved many traditions:

- New Year’s Day visits (first-footer customs)

- Harvest suppers

- Community dances (fiddles, reels, and jigs)

- Outdoor picnics with footraces and games

- Spinning and quilting bees

- Hog-killing and butchering days

- Maple syrup season visits

Kids lived for these events. Photographs, newspaper accounts, and memoirs from this period describe:

- boys skipping stones in the Mississippi River

- footraces (James later credited his athletic build to farm life)

- girls gathering wildflowers and helping prepare food

- older students organizing games for younger ones

My family would have been right in the thick of it.

And so would James.

The 1875 Bennie’s Corners Squirrel Hunt; And My Ancestor as Captain

This event says everything about rural life at the time.

In 1875, the local paper reported a massive “squirrel hunt” … a competitive gathering where men and boys hunted all manner of forest creatures for points.

Captains that year were:

- John Snedden

- Robert McKenzie — my 2nd great-granduncle

The count included squirrels, chipmunks, woodpeckers, crows, skunks, foxes — everything had a point value.

Over 2,500 animals were tallied.

James would have been 14 at the time, prime squirrel-hunt age.

The event ended with a dance at the Snedden home.

These were our ancestors’ community traditions, and James grew up inside them.

(side note – they danced and partied after culling 2,500 animals ☹)

So, What Does All of This Really Mean?

James would have shared a school, a playground, walking routes, church pews, and likely chores and games with my McKenzie (and Leckie) family.

This is not speculation; it’s exactly how rural Ramsay Township functioned. They were part of everyday rural life around Bennie’s Corners:

- attending Sabbath services

- gathering for Christmas and fall picnics

- working cooperatively at harvest time

- participating in the famous 1875 Bennie’s Corners Squirrel Hunt

- attending township meetings and seasonal fairs

- walking the same concession roads the Naismith children used daily

In communities like this, families didn’t just know one another.

They depended on one another.

My ancestors were part of the same community that raised James.

They knew his family.

They lived beside them.

Their children grew up with him.

They sat in the same classroom.

They were the neighbours whose farms bordered the Young homestead where James lived after becoming orphaned.

This is not a genealogical footnote.

This is a shared heritage.

My ancestors helped build the world that produced James Naismith … the values, the work ethic, the Scottish Presbyterian culture, the sense of community, the emphasis on physical play and outdoor life.

Those things made him.

And those things came from my people, too.

Why This Discovery Means So Much to Me

Most genealogy focuses narrowly on direct lineage. But real historical storytelling recognizes that community is lineage.

My ancestors weren’t just names on certificates.

They were part of the landscape: the roads, the mills, the pews that formed one of Canada’s most influential sons.

That’s the real connection.

And it’s stronger and more meaningful than simply sharing DNA.

Somewhere in that little pocket of rural Canada…

… the future inventor of basketball was playing, learning, laughing, and growing up beside my McKenzie (and Leckie) ancestors.

And for me, that changes everything.

Leave a comment