Hello and welcome to my newest genealogy blog! Today, I want to share the story of my grandfather, Benjamin George Richards, and his remarkable life, with a particular focus on his service during the Second World War as a Canadian soldier.

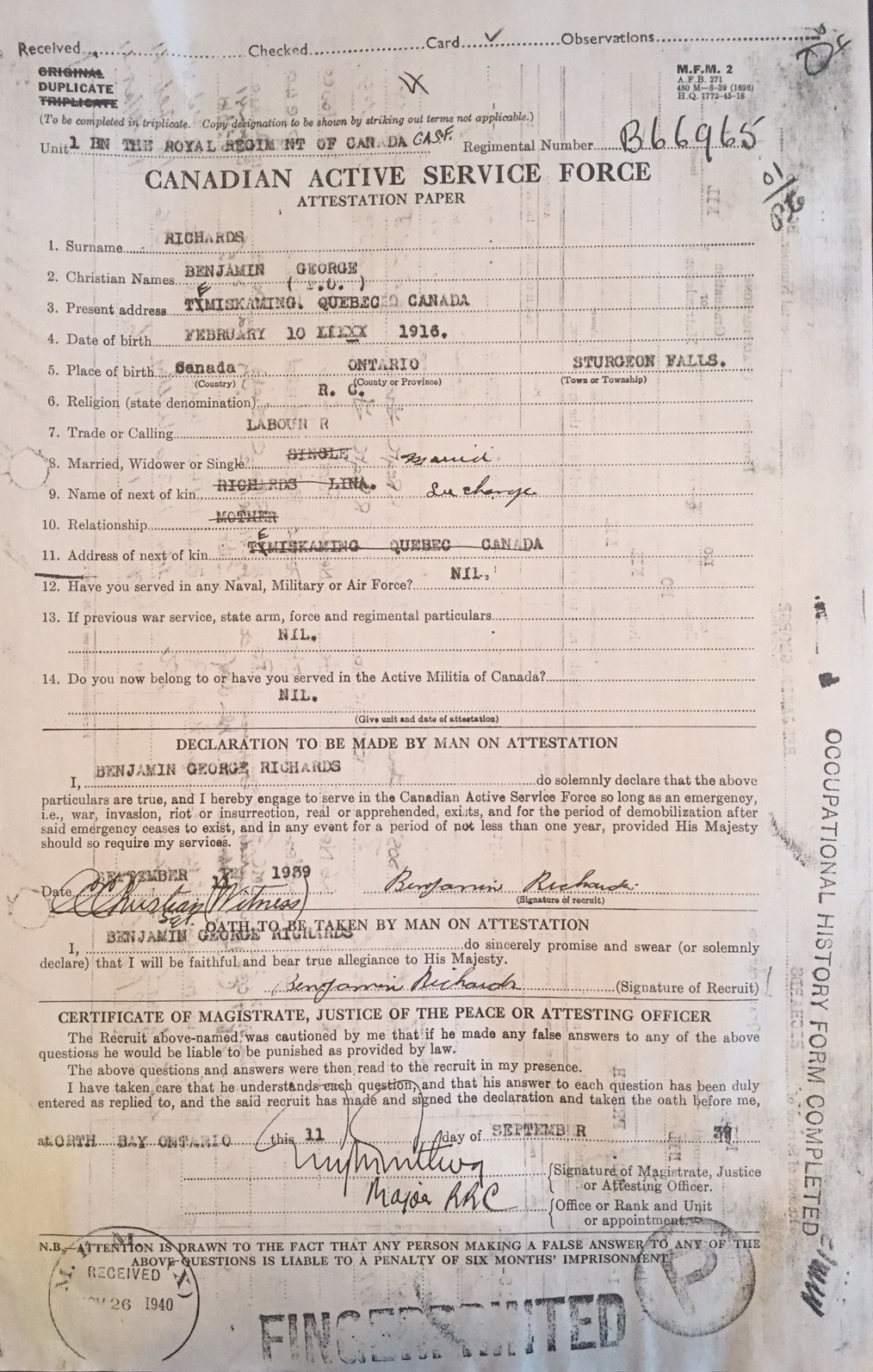

A few years ago, I requested a copy of Grampa’s military records from the Department of Veterans Affairs (Canadian Armed Forces). Unlike modern military service files, WWII records are still not available online, so obtaining the original hard copies was a true treasure for my family history research.

Military records are a wealth of information. They detail enlistment, pay, postings, transfers, hospital admissions, disciplinary actions, training, and discharge information. Grampa’s records, handwritten with dense abbreviations, were initially overwhelming. To make sense of the acronyms (over 7,500 unique ones exist), I had to reference guides summarizing WWII Canadian military terminology.

Early Life

Benjamin George Richards was born February 10, 1916, in Sturgeon Falls, Ontario. His father, Ambrose Richards, was 28, and his mother, Bridget Mullen, was 29.

Military records indicate that he completed Grade VIII and was bilingual in English and French. From 1933 until his enlistment, he worked at the Canadian International Paper (CIP) Company in Témiscaming, Québec, starting as a general labourer and eventually becoming a machine tender.

His hobbies and pastimes were listed as skiing, skating, playing 1st base in baseball/softball, and performing music on the banjo, guitar, and mandolin.

Military Service

Benjamin Richards enlisted in the military on September 11, 1939, at North Bay, Ontario, citing “patriotic reasons.” He joined The Royal Regiment of Canada as a Private, Infantry, with regimental number B-66965. Capt. R. Robillard described him as “average intelligence – should be ok for Carriers.”

His service record spans five years and includes details of postings, pay, hospital admissions, and disciplinary actions. Below is a chronological summary of his service, highlighting the most salient points.

Chronological Record of Service

Sept 1, 1939: The Royal Regiment of Canada, CASF, mobilized at the outbreak of WWII.

Sept 11, 1939: Enlisted at North Bay, Ontario, as a Private in the Infantry. citing “patriotic reasons”. Royal Regiment of Canada.

June 10, 1940: Embarked from Halifax for garrison duty in Iceland with “Z Force.” Now, this is actually an interesting story and part of history. As I was going through Grampa’s personnel file, I noticed that, besides one entry showing he embarked for the United Kingdom, all it said was “SOS Z Force.” I remember thinking, “What the heck was this Z Force?”

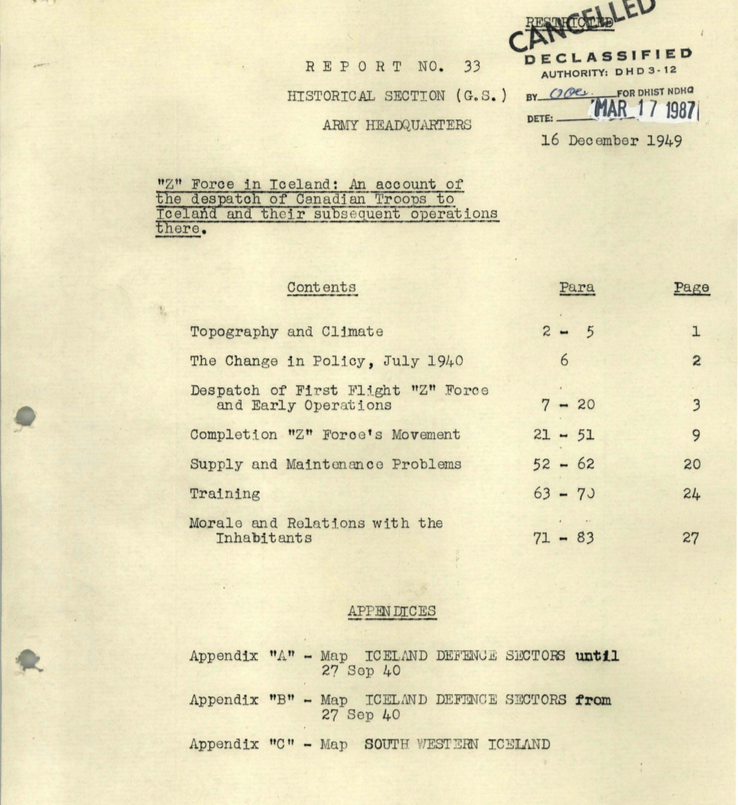

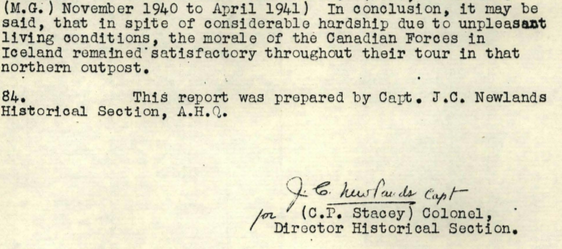

So, I did a Google search and discovered that it was a British Canadian garrison force in Iceland. I was pointed to a fascinating document, declassified on March 17, 1987, entitled “Z Force in Iceland: An Account of the Despatch of Canadian Troops to Iceland and Their Subsequent Operations There.” The report details the activities of the Canadian Army Z Force from its dispatch to Iceland on June 10, 1940, until its departure on April 28, 1941.

Canada was an occupying military power in one of the smallest and most isolated countries in the world. How? Why? Well, when war broke out in September 1939, Denmark and Iceland jointly declared their neutrality (Iceland had been granted autonomous status from Denmark after WWI).

But the Nazis had been showing interest in Iceland throughout the 1930s—sending trade missions, flying instructors, and even teams of German “anthropologists” roaming the island.

As quickly as possible, Canada put together a military expedition mysteriously dubbed “Z Force.” So, Canada was in Iceland to defend it against a possible German attack!

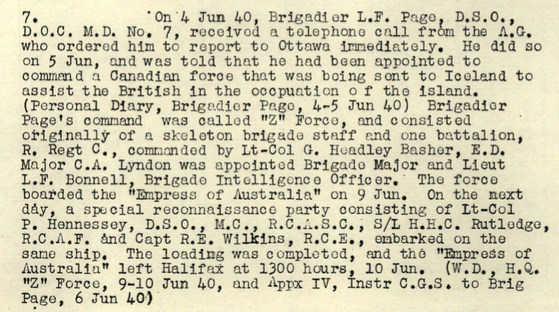

This snippet from the report mentions that Grampa was part of the initial Z Force, commanded by Lt-Col G. Headley Basher. The force boarded the Empress of Australia on June 9 and departed at 1:00 pm on June 10. The Royal Regiment of Canada was the only infantry battalion in this initial force, armed with 12 Lewis machine guns.

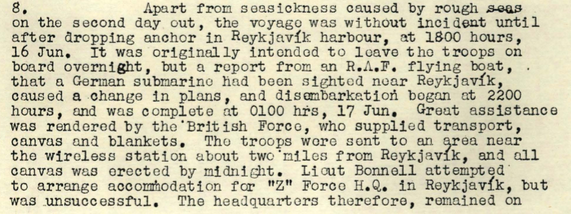

June 16, 1940: Disembarked Reykjavík, Iceland

The Royals were ferried ashore and marched through silent streets to set up tents (which were later replaced with metal Nissen huts) near the local airfield that British engineers had begun expanding. Within days, the British brigades packed up and sailed back to rejoin the war.

While in Iceland, Benny was a member of C Company—I almost missed this detail, as it was mentioned on only one page under Current Service: “R.R.C. Rgmt C Coy.”

The Empress of Australia, meanwhile, sailed back to Halifax where the rest of Z Force had been assembled. That secondary force consisted of two more battalions — the Cameron Highlanders and les Fusiliers Mont-Royal who arrived in Iceland on July 9, 1940.

The report indicates the supply and maintenance problems while they occupied Iceland.

Only the Royal Regiment of Canada brought its own vehicles, so when the second flight of troops arrived on July 7 without vehicles, they had to hire civilian trucks, which caused delays until the S.S. Tregarthen arrived on July 27—taking 16 days to unload.

Other issues included clothing (the British coats were superior; the Canadian sheepskin coats were almost always wet), and the need for 3-foot steel tent pegs, as the ground was frozen and winds nearly gale force.

We know that he was in C Coy but not which platoon in that company he was in, but we do have an idea of what training looked like.

The biggest threats to the Canadians weren’t enemy soldiers—they were the cold (it snowed in August 1940) and the local moonshine, known as “Black Death.”

In total, Z Force amounted to 2,659 Canadian soldiers stationed in Iceland. Eventually, the order was given for the bulk of Z Force to leave for Britain. They were relieved by the 70th British Infantry Brigade.

Oct 26, 1940: Embarked on the Empress of Australia

Oct 31, 1940, at 10:30 a.m. the ships weighed anchor and put out for the UK, leaving Iceland behind. A small force was left behind (Cameron Highlanders).

The graves of 41 Canadian soldiers, seamen and airmen who died in Iceland during the war are still tended carefully in a cemetery near the airport they defended.

A note from the report sums it up perfectly: “…the morale of the Canadian Forces in Iceland remained satisfactory throughout their tour in that northern outpost.”

Nov 3, 1940: Grampa disembarked somewhere in the United Kingdom, but his records don’t specify the exact port or camp. Most Canadian units during that period arrived in southern England—ports like Liverpool, Glasgow, or Plymouth were common. After disembarkation, troops were usually sent to temporary camps for accommodation, processing, and initial training.

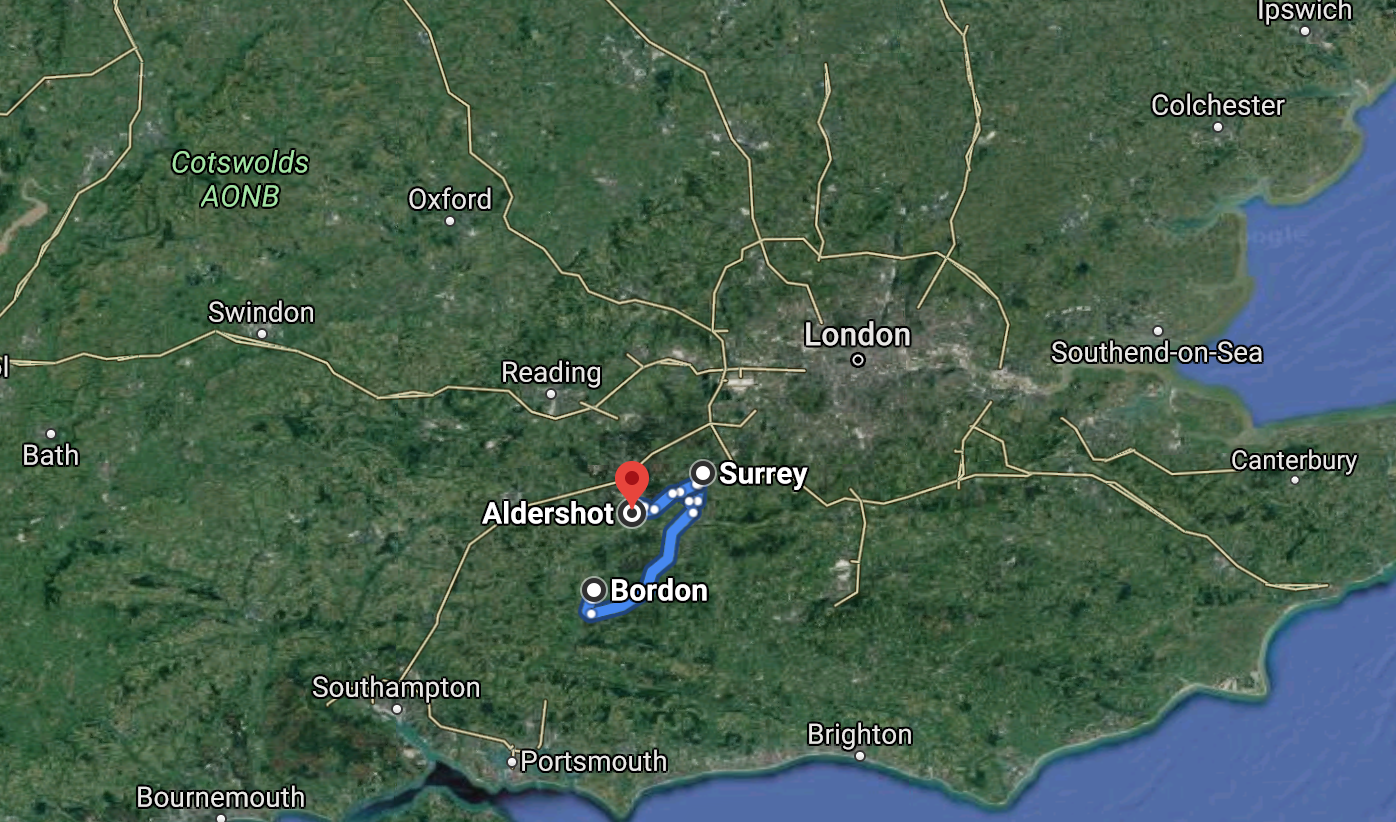

Nov 7, 1940: His unit was re-designated as the 1st Battalion, Royal Regiment of Canada, CASF, when a 2nd Battalion was formed to provide reinforcements. This suggests that between Nov 3 and Nov 7, he was likely at one of the Canadian Army reception/training camps in the UK, probably in the Aldershot Command area, which included Witley, Bordon, and Bramshott. These were the main camps for processing and training Canadian soldiers arriving in Britain. So, while the record doesn’t state a specific location, it’s highly probable he was at one of those three camps, being prepared for service with the 1st Battalion.

Dec 9–16, 1940: Admitted to and discharged from CMC Bordon hospital.

Jan 17, 1941: Confined to barracks (CB) for 4 days for a first offence under Army Act Sec. 19 – drunkenness. This didn’t necessarily mean he was drunk on duty—just that military rules considered drinking in uniform or on base a punishable offence, even for a first-time lapse.

Feb 10–18, 1941: Hospital admission.

April 1, 1941: Forfeited 5 days’ pay for being absent without leave (AWL) for 1 hour 36 minutes.

Feb 25–March 4, 1942: Hospital admission and discharge.

Feb 27 – Aug 26, 1942: During this period, Grampa was part of the 2nd Canadian Divisional Infantry Reinforcement Unit (2 CDIRU), serving on Carrier as a Carrier Instructor.

Now, here’s where it gets really interesting. The 2 CDIRU was a major training and reinforcement unit for the 2nd Canadian Infantry Division, the same division that would later lead the Dieppe Raid on 19 August 1942. The raid involved a massive amphibious assault on the French port of Dieppe, with Canadian troops assigned to four beach sectors. At Blue Beach, near Puys, soldiers from the Royal Regiment of Canada and the Black Watch were delayed and pinned down under devastating machine-gun and artillery fire.

Here’s the important clarification:

Although the 2 CDIRU supplied trained reinforcements to the division, there is no evidence in Grampa’s records that he personally landed at Dieppe. His files don’t specify his exact location on the day of the raid, so all Dieppe details should be understood as context for the unit he was attached to, not his personal experience.

What we do know is that Grampa was actively involved in training and preparing soldiers. During this time, he attended:

- Carrier Course (Class A): March 18 – April 18, 1942

- Motorcycle Course: August 8 – August 22, 1942

So, what did being a Carrier Instructor actually mean?

- The Universal Carrier, sometimes called the Bren Gun Carrier, was a small, lightly armoured tracked vehicle used to transport troops, carry weapons and ammunition, evacuate casualties, and perform reconnaissance.

- Each Carrier typically had a crew of four soldiers: a driver-mechanic, an NCO or commander, and two riflemen or gunners.

- As a Carrier Instructor, Grampa’s job was to train soldiers in driving, operating weapons, and maintaining these vehicles. He also taught tactical use, showing soldiers how to move supplies, support infantry, and evacuate wounded under realistic and sometimes hazardous conditions

Although many people think they were small tanks, they actually weren’t. These vehicles were small, tracked, lightly armoured utility carriers used for an incredible range of tasks.

✦ His role as a Carrier Instructor

As an instructor, Grampa taught soldiers how to:

- drive and operate tracked vehicles

- fire and reload the Bren gun from the Carrier

- read terrain and navigate under combat conditions

- perform field maintenance and repairs

- use the Carrier safely in tactical operations

- transport wounded and supplies under fire

In short, he trained the men who supported and sustained the fighting infantry, ensuring troops had mobility, fire support, and logistical backup. His work was essential to front-line soldiers’ survival — even though he wasn’t fighting directly on the front lines himself.

I’m still working on accessing his unit’s Troops War Diaries, which may reveal exactly where he was stationed during these months. For now, what we know with certainty is that Grampa’s role was hands-on, technical, and deeply important to Canada’s war effort — a quiet but vital contribution behind the scenes of major operations like Dieppe and beyond.

Aug 27 – Oct 9, 1942: During this period, Grampa was officially assigned to the Regimental Headquarters (HQ) Company of the Royal Regiment of Canada as a Carrier Driver.

Even though Grampa is listed at times as a Carrier Driver, that doesn’t mean he was fighting on the front lines. Universal Carriers weren’t only used in battle — they were used constantly in England for training exercises, base operations, moving equipment, transporting troops between camps, and mechanical test runs. Because he was trained as both a Driver Mechanic and a Carrier Instructor, his role was to operate these vehicles in a training environment, maintain them, and help prepare other soldiers to use them. His service records show no deployment to active combat zones, so we know he wasn’t driving Carriers in battle — but he was absolutely part of the war effort, overseas for nearly five years, doing the essential behind-the-scenes work that allowed combat units to function. His contribution was real, necessary, and part of the larger machine that kept the Canadian Army running.

Why Was Grampa a Carrier Driver After Being a Carrier Instructor? He was actively working with the vehicle he had just finished teaching others to use. Instructors were often rotated into active platoon duties to keep their skills sharp. He was a Driver/Mechanic which made him an ideal prototype carrier driver, and the army uses personnel where they needed them the most.

The record notes “H (20 days)”, which typically indicates hospital or home leave. In practical terms, this means that for about 20 days during this period, Grampa was temporarily away from active duty—likely for rest, recovery, or a minor health issue—but he remained officially attached to HQ Company.

Oct 10, 1942 – [date unspecified]: After his assignment with the Regimental Headquarters Company, Grampa returned to the 2nd Canadian Divisional Infantry Reinforcement Unit (2 CDIRU). His records note that he was performing “general fatigues.” Now, that might sound mysterious, but in military terms, general fatigues simply means practical, hands-on work that keeps a unit running.

March 17, 1943: Grampa was officially granted a daily rate of $1.50. That’s right—$1.50 a day. It seems almost laughable today, but back then this was typical pay for a Private in the Canadian Army.

Soldiers didn’t need to worry about rent, meals, or many daily necessities—the military provided housing, food, uniforms, and equipment. Still, this small sum was his official compensation for performing his duties, which at the time included training and instructing soldiers on Universal Carriers.

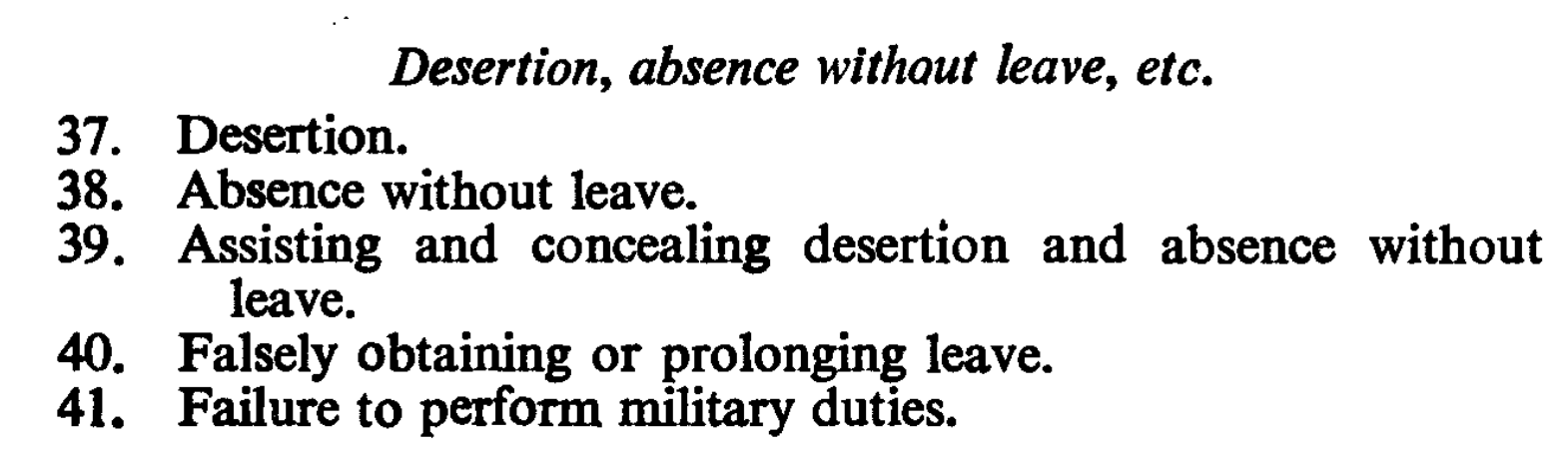

Dec 28, 1943: Awarded 8 days CB and 8 days’ pay under Sec 40 of AA – I had to do some research here. The Gov’t of Canada, Library and Archives Canada website has S.40 under Miscellaneous Military Offences – “Acting to the Prejudice of Good Order and Military Discipline”. What I’ve been able to ascertain is that it may have been for: Falsely obtaining or prolonging leave aka he was AWOL.

Jan 15, 1944: On this day, Grampa was awarded the Canadian Volunteer Service Medal (CVSM). This medal was granted to members of the Canadian Naval, Military, or Air Forces who voluntarily served on active duty and completed at least eighteen months of honourable service between September 3, 1939, and March 1, 1947.

What makes it even more meaningful is the silver clasp with a maple leaf at its center, awarded for 60 days of service outside Canada. For Grampa, this reflected his overseas service in Iceland and the United Kingdom, recognizing both his commitment and the sacrifices he made while away from home.

May 30, 1945: Grampa was granted official permission to marry Miss Sally Anne Lee, with the wedding set for on or after June 14, 1945. During the war, Canadian soldiers serving overseas had to request formal permission from their commanding officers to marry. This ensured the army could manage service commitments, leave, and post-war planning. For Grampa, this permission marked the beginning of a new chapter in his life, balancing his military duties with personal milestones even before the war officially ended.

June 20, 1945: Grampa married Miss Sarah Ann Lee in Agbrigg, Yorkshire, England, just as he had been given permission to do. Following the wedding, he officially changed his next-of-kin to his new wife, listing her as Mrs. Sarah Ann Richards of 14 Pick Hiss Rd, Meltham, Yorkshire, England.

Aug 18, 1945: Grampa was granted 30 days disembarkment leave, from August 18 to September 16, 1945, with a small per diem of $0.50 per day.

Even though the war wasn’t officially over until September 2, 1945, this leave makes perfect sense. By mid-August, Germany had surrendered and Japan had just surrendered on August 15, so hostilities were effectively over. The military began transitioning soldiers back from overseas, giving them time to travel home, take care of personal matters, and prepare for civilian life.

For Grampa, this leave meant a brief period to catch his breath after years abroad and spend time with his new wife, Sally, perhaps enjoying their first days of married life together. It was a formal step in the demobilization process, bridging his military service and the life that awaited him back home.

Sept 2, 1945: The Second World War officially came to an end. After nearly six years of global conflict, soldiers like Grampa had finally reached the point where their service overseas was complete. For Grampa, this marked the closure of one of the most intense chapters of his life—from garrison duty in Iceland to training and instructing on Carriers in the UK, enduring harsh conditions, strict discipline, and long months away from home. Now, with the war over, the focus shifted to returning home, reuniting with loved ones, and beginning civilian life alongside his new wife, Sally.

Sept 21, 1945: Grampa was officially struck off strength (SOS) on discharge from the Canadian Army. Along with his discharge, he received a clothing allowance to replace uniforms and gear, and rehabilitation benefits to help him transition back into civilian life.

Dec 31, 1945: After the Second World War had officially ended, the Royal Regiment of Canada was disbanded and reverted back to Reserve status.

Of all the 20+ pages of Grampa’s military records, I could only pinpoint three camps he was stationed at in the UK—the rest simply list “UK.” Those camps were Witley, Bordon, and Aldershot, and each played a unique role in preparing Canadian soldiers for service overseas.

Witley Military Camp was a temporary Canadian Army camp on Witley Common, Surrey. It served as a hub for training, instruction, and accommodation of troops newly arrived in the UK. Here, Grampa would have been training soldiers on driving and maintaining Bren and Universal Carriers, keeping vehicles in working order, and preparing his platoon for operational readiness.

Camp Bordon, with its long-standing Canadian Army association, functioned as a training and staging area. At Bordon, Grampa’s work likely continued as Carrier Driver and Instructor, preparing reinforcement units, maintaining vehicles, and supporting administrative and logistical duties—ensuring that both men and machines were ready for deployment.

Camp Aldershot was one of the largest Canadian Army processing and training centres in the UK. About 330,000 Canadians passed through during the war. Here, Grampa would have been involved in instructing new reinforcements, coordinating vehicle readiness, and helping organize troop movements and exercises. While not a frontline camp, his work was essential in keeping soldiers and equipment prepared for action.

I’ve mapped out the 3 places I was able to place him. Surrey, Aldershot and Bordon.

In total, Grampa was overseas for 62 months, serving in Iceland and the UK, before being discharged on September 21, 1945, in Toronto, Ontario, at the age of 29

According to his Discharge Certificate and his Record of Service, he is “to return to civil life – on demobilization”. His physical description at the time of discharge from service was “brown eyes and brown hair. Fair complexion. Burn scar on right axillae; scar 1.5″ x 1″ on inside of lip”.

His CONFIDENTIAL Discharge Papers note his future plans “I am returning to my former job as a machine tender”.

The military’s recommendation on discharge were as follows:

“A recently married man, 29 years of age, medium build, average appearance. Seems pleasant, steady, reliable labour type”.

It also noted his family situation:

“Richards states that his mother and sister are living in Temiskaming; father has been confined to hospital for about four years. Richards married in England and expects his wife to join him in a few months. They can live with his mother until they secure a house through the paper company, who are building homes for returning service personnel.”

If returning as a Machine Tender was not possible, Grampa planned to seek employment as a Truck Driver.

Post Military Life

He and Sally went on to have seven children during their marriage. From conversations with my uncle Kenny and my aunt Gwen (I wish my dad were still alive so I could ask him some of this), I learned that around 1955 they moved into 102 Anvik Avenue.

At that time, Témiscaming was a company town, owned almost entirely by Canadian International Paper (CIP)—including the homes. The company eventually sold the houses around 1972, and Sally and Benny purchased theirs.

The row house was tiny—only four rooms in total: a living room, kitchen, two bedrooms, and a single washroom. It was two stories, with no basement, though Aunty Gwen remembers that they dug one out until they hit a large rock—enough to fit the furnace down there.

Only the front bedroom had closet space, so Grampa built one in the back room for the three girls, along with a double bed. The bathroom had a toilet and bathtub but no sink, and there was an enclosed, unheated back porch. The entire home was about 600 square feet, housing nine people: seven kids and two adults.

Interestingly, the house was originally 502 Elm Avenue, but after Dutch Elm disease wiped out the trees, the town renamed the street Anvik Avenue and renumbered the houses, so their address became 102 instead of 502.

Benjamin Richards passed away on June 17, 1977, in Montréal, Quebec, at the age of 61. He suffered a coronary thrombosis while visiting his daughter Gwen, her husband Serge, and their son Marc.

I was only three years old when Grampa passed away, so unfortunately, I don’t have any memories of him. I’m not even certain if I have any photos of the two of us together.

Afterward, Gramma Sally sold the house to Lucien Bernard for $6,000 in 1978 and moved to Verdun, Quebec, to live with her daughter Gwen, her husband Serge, and their children, Marc and Caroline.

One of the most rewarding challenges in my genealogy journey has been writing about these family stories and preserving these legacies, so they aren’t lost to time.

I plan to compile these blogs into a family history book. I’m deeply passionate about recording and sharing family stories, and I encourage everyone to do the same whenever they have the chance.

As I continue to investigate Benny’s time in WWII, I will keep updating this blog with new findings and insights.

Leave a comment