I can be quite obsessive at times. My latest pastime is genealogy. I’ve been working on my family tree for years, but now I work on it obsessively, almost daily. My interest is both historical and philosophical:

Where do I come from? How am I here, literally and figuratively?

People who do genealogy have a basic desire to know where they came from and how they got to where they are today. The knowledge that my ancestors had great inner strength is a powerful motivator for trying to understand my place in the world. I mean, if it weren’t for them, I wouldn’t be here today typing these words.

I look at genealogy as history on a personal scale. It’s truly a journey of many lifetimes and lifelines from the past to the present and into the future. It’s about discovering your heritage, creating a story about your family, and leaving meaningful legacies for future generations. At this stage of their lives, my children really don’t give a hootenanny about our roots, and in all honesty, neither did I at their ages. But as I’ve aged and gone through life experiences, I’ve wondered more and more.

Some lines I’ve been able to trace back to the 1500s and 1600s, back to England and France, to those who came to settle the New World. One of my ancestors was a Fille du Roi (King’s Daughter). I have family who founded parts of the eastern United States, while others lived in Salem, Massachusetts, and was an accuser during the Salem Witch Trials. I had a great-uncle who was KIA in the Great War. I have my great-grandfather’s and grandfather’s military records and their units’ war diaries, and I’ve been able to track them through their battles in both WWI and WWII. I’ve found my grandmother’s arrival records on the Aquitania from when she arrived in Canada in 1946 as a War Bride.

I’ve found so many fascinating things in my family history on both sides, down all four lines. It makes it all the more interesting when you know you have a personal connection to these people.

A few weeks ago, I submitted my DNA to Ancestry.ca. Genetic genealogy is a way for people interested in family history to go beyond what they can learn from relatives or historical documentation. Examination of DNA variations can provide clues about where a person’s ancestors might have come from and about relationships between families. They’ve confirmed receipt — now all I have to do is wait patiently another 6–8 weeks for the results. Stay tuned!

We inherit from our ancestors gifts so often taken for granted. Each of us contains within this inheritance of soul. We are links between the ages, containing past and present expectations, sacred memories, and future promise.

— Edward Sellner

Acknowledging History Honestly

I have so many cool things to share, and today I’m going to share the story of my relationship to one of the early architects of colonial New France (for those reading from elsewhere, what would later become Canada). I can only be a certain percentage proud of this, since no European actually “discovered” North America; Indigenous peoples (les Peuples autochtones) were here long before any European claims were made. I acknowledge and honour that.

Put on your history caps, folks, we’re heading back to the 1600s.

You may not remember much from grade-school history, but you might recall explorers like Jacques Cartier, Louis Frontenac, Étienne Brûlé, or Samuel de Champlain, who founded Québec City. The super cool thing is that I do remember. Being French Canadian, we learned all about this in elementary school: les premiers colons, Marguerite Bourgeoys, les Amérindiens, les seigneuries, les Jésuites. And yes, I most certainly remember learning about Samuel de Champlain and the first settlers.

Olivier Le Tardif

The first of my ancestors to come to la Nouvelle-France / New France was a contemporary of Champlain’s. Olivier Le Tardif (sometimes spelled simply Tardif) was my 12th great-grandfather in the Lamothe line, and I can also trace descent from him in the Duchesne line through his son Guillaume.

A bit about Le Tardif: (c. 1603–1665), he was the son of Jean Le Tardif and Clémence Houart, born at Étables-sur-Mer, a seaside village on Saint-Brieuc Bay in Brittany, France. He embarked from Honfleur on May 24, 1618, aboard a ship of the Company of Merchants that was returning Samuel de Champlain to the colony.

Le Tardif became one of Champlain’s trusted interpreters, working in the languages of the Huron, Algonquin, and Montagnais (Innu) peoples. During the 1629 capture of Québec City, it was Olivier Le Tardif, acting on Champlain’s authority, who formally delivered the keys of the city to Louis and Thoma

Early Colonial Québec and Intersecting Lives

While Olivier Le Tardif served as general clerk of the Compagnie des Cent-Associés (Hundred Associates) in Québec—and while his first wife, Louise Couillard, was still alive, he became the godfather and guardian of Marie-Olivier Manitouabe8ich.

Marie-Olivier Manitouabe8ich is recognized as the first documented Indigenous woman to enter into a Catholic church marriage with a French settler in New France, when she married Martin Prévost in 1644. This is where the story becomes even more remarkable: she is also my ancestor, through another family line.

Le Tardif’s Second Marriage and My Lineage

For this particular branch of my family, my descent comes from Le Tardif’s second marriage, which took place on May 21, 1648, while he was back in France. He married Barbe Émard (also recorded as Aymard), the widow of Gilles Michel. His first wife, Louise Couillard, had died several years earlier.

Olivier brought Barbe to Château-Richer, where they settled and raised their family. Together, they had three children.

Remarkably, I descend from two of those children, but through two different sides of my family—my maternal grandmother’s line and my maternal grandfather’s line, who eventually married one another.

Olivier LE TARDIF (abt 1604-1665) + Barbe ÉMARD (1625-1659)

Gen 1: Barbe Delphine LE TARDIF (1649-1702) + Jacques CAUCHON DIT LAMOTHE (1635-1685)

Gen 2: Jean Cauchon + Anne Bollard

Gen 3: Francois Cauchon dit Lamothe + Marie Francois Houde

Gen 4: Francois Cauchon dit Lamothe +Marie Laroche Rognon

Gen 5: Pierre Lamothe + Marie Anne Senet

Gen 6: Magloire Lamothe + Seraphine Gauthier

Gen 7: Joseph Lamothe + Marie Louise Charron

Gen 8: Emile LAMOTHE + Marcella Houle

Gen 9: Clifford LAMOTHE + Desneiges Duchesne

Gen 10: Mona Lamothe + Patrick RICHARDS

Gen 11: MOI

-AND-

Olivier LE TARDIF (abt 1604-1665) + Barbe ÉMARD (1625-1659)

Gen 1: Guillaume LE TARDIF (Jan 30 1656) + Marie Marguerite GAUDIN (Mar 1665-?)

Gen 2: Charles TARDIF + Marie Genevieve Le Roy

Gen 3: Jean Roch TARDIF + Marie Louise Grenier

Gen 4: Jean Baptiste TARDIF + Marie Felicite Rancourt

Gen 5: Brigitte Tardif + Charles BINET

Gen 6: Philomène Genevieve Binet + Charles BINET

Gen 7: Philomène Adelphine Binet+ Honore TRUDEL

Gen 8: Leda Trudel + Mederic Duchesne

Gen 9: Palma DUCHESNE + Laurette Allard

Gen 10: Desneiges Duchense + Clifford LAMOTHE

Gen 11: Mona Lamothe + Patrick RICHARDS

Gen 12: MOI

Where Our Lines Intersect: The Story of Marie‑Olivier Sylvestre

Now, to add to this story, let’s explore where these lines intersect and cross further.

Roch Manitouabeouich was Indigenous and worked as a scout and interpreter for Olivier Le Tardif, who was an agent for Samuel de Champlain, representing la Compagnie des Cent-Associés in the fur trade. There is debate among historians about whether Roch was Huron, Algonquin, or Abenaki, but what is clear is that he was highly skilled in multiple native languages — a crucial asset in early New France. He was also a friend of Le Tardif and had been converted to Christianity by French missionaries. In the baptismal ritual, he received the Christian name Roch, in honor of Saint Roch, patron saint of dogs, the falsely accused, and bachelors, among others.

Roch and his wife, Oueou Outchibahanouk, had a daughter who was baptized by Jesuit missionaries as Marie. The records describe her as the daughter of “Manitouabeouich Abenaquis,” indicating Indigenous heritage. Olivier Le Tardif became godfather to the baby girl, and in keeping with contemporary custom, he gave her his own name, Olivier. The Jesuit missionary performing the baptism also recorded the name Sylvestre, meaning “one who comes from the forest” or “one who lives in the forest.”

At ten years old, Marie‑Olivier was placed under the care of Olivier Le Tardif. While she never formally carried his surname, this arrangement allowed her to be educated as a French girl of status. She first boarded with the Ursuline nuns in Québec and later lived with a French family, Sieur Guillaume Hubou, where she received private tutoring.

As a young woman, Marie‑Olivier married Martin Prévost, a close friend of the Hubou family and of Olivier Le Tardif. Their marriage, celebrated on November 3, 1644, in Québec, is the first documented Catholic marriage between an Indigenous woman and a French settler in New France. Witnesses included Olivier Le Tardif and Guillaume Couillard, Le Tardif’s father‑in‑law.

Olivier Le Tardif died in 1665 at Château Richer, after a period of premature senility, though he had moments of lucidity to the very end. He was buried under the church of Notre-Dame de Bonne Nouvelle in Château Richer.

Marie‑Olivier and Martin Prévost had nine children, though tragedy struck when three of their children, Ursule, Marie Madeleine, and Antoine, died on the same day in 1661. Marie herself passed away at 37 years old, shortly after giving birth to her last child, Thérèse. Her marriage certificate notes that she was born in Huron territory, Sillery, though there are no recorded details of her parents’ deaths.

Martin Prévost was one of the pioneers of Beauport, near Québec. Born in 1611 to Pierre Prévost and Charlotte Vien of Montreuil-sur-le-Bois-de-Vincennes (now Montreuil-sous-Bois, near Paris), he appears in Québec records as early as 1639 and died on January 26, 1691, at Beauport.

This story reminds us that history is complex and full of intersecting lives, Indigenous and European alike. Marie‑Olivier Sylvestre’s life illustrates the deep and often overlooked connections between early French settlers and the Indigenous peoples of New France.

So, this is how I descend from the 1st documented marriage between a French settler to the new colony and an indigenous woman, as follows. Follow along carefully because the lines cross here, too!

- Roch Abenaki Manitouabeouich + Outchibahabanouk Oueou

- Marie-Olivier-Sylvestre Manitouabeouich. + Martin Prévost

- Jean-Baptiste Prévost + Marie Anne Giroux

- Catherine Prévost + Charles Petitclerc

- Charles Petitclerc + Marguerite Meunier

- Joseph Trudel + Magdelaine Langlois

- Joseph Trudel + Josephine Proteau

- Honore Trudel + Philomène Adelphine Binet

- Leda Trudel + Mederic Duchesne

- Palma Duchesne + Laurette Allard

- Desneiges Duchesne + Clifford Lamothe

- Mona Lamothe + Patrick Richards

- MOI

Intersecting Lines of History: From New France to Louis Jolliet

Now, if you’re following along, you’re beginning to see how fascinating it is when these early lines of my ancestors intersect. Let’s take it one step further.

Martin Prévost settled at Beauport as an “habitant,” or farmer. He had at least nine children with his first wife, Marie-Olivier-Sylvestre Manitouabeouich, who was Indigenous and considered one of the first documented Native women to marry a French colonist in New France. Marie-Olivier-Sylvestre passed away relatively young, shortly after giving birth to her last child, Therese.

After her death, Martin Prévost remarried. Historical records confirm he married a woman named Marie d’Abancourt, though sources differ on whether she was the widow of Jean Jolliet, father of the famous explorer Louis Jolliet. Some genealogical traditions suggest this connection, but there is no definitive primary source confirming that Martin Prévost was Jolliet’s stepfather. I mention it here as a fascinating family tradition worth noting.

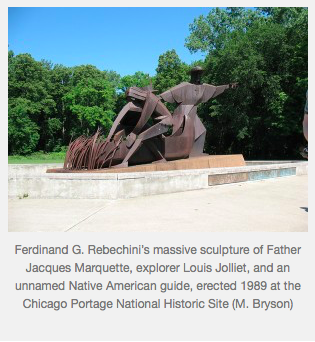

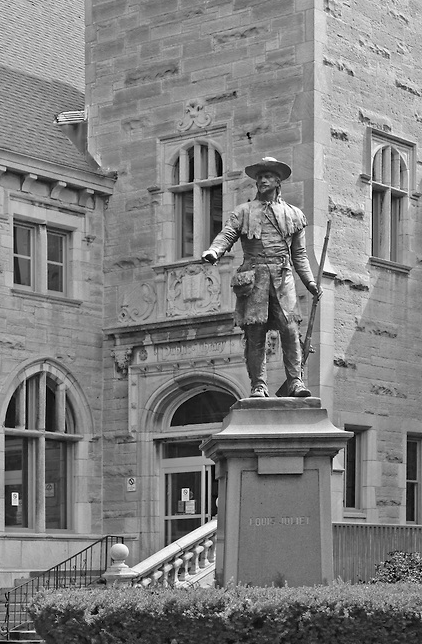

Speaking of Louis Jolliet, he is the explorer many of us remember from history class. Born in 1645 in Quebec, Jolliet is best known for his 1673 expedition with Jacques Marquette, a missionary and linguist. Together, they explored the upper reaches of the Mississippi River, mapping its course and establishing contact with Indigenous nations, hoping to find a route to Asia. While Hernando de Soto was the first European to record the Mississippi’s entrance in 1541, Jolliet and Marquette were the first to map and travel most of its length.

Some dramatic stories from their return journey mention dangerous rapids near Lachine, and while some details—like a capsizing canoe—are documented, other elements, such as the death of a chief’s son, appear mainly in secondary accounts. What we do know is that Marquette’s journal became the authoritative record of their journey, as Jolliet’s own records were partially lost.

Jolliet’s legacy lives on in the Midwestern United States and Quebec, through place names like Joliet, Illinois; Joliet, Montana; and Joliette, Quebec, the latter founded by one of his descendants, Barthélemy Joliet.

So there you have it, a vivid intersection of my family history and the broader history of New France. Even if some connections, like Martin Prévost’s possible step-parenting of Louis Jolliet, remain in the realm of tradition rather than documented fact, it’s exciting to see how these stories weave together across centuries.

Who said history or genealogy is boring? Do any of you have intriguing family connections or historical ties? I’d love to hear them.

Leave a comment